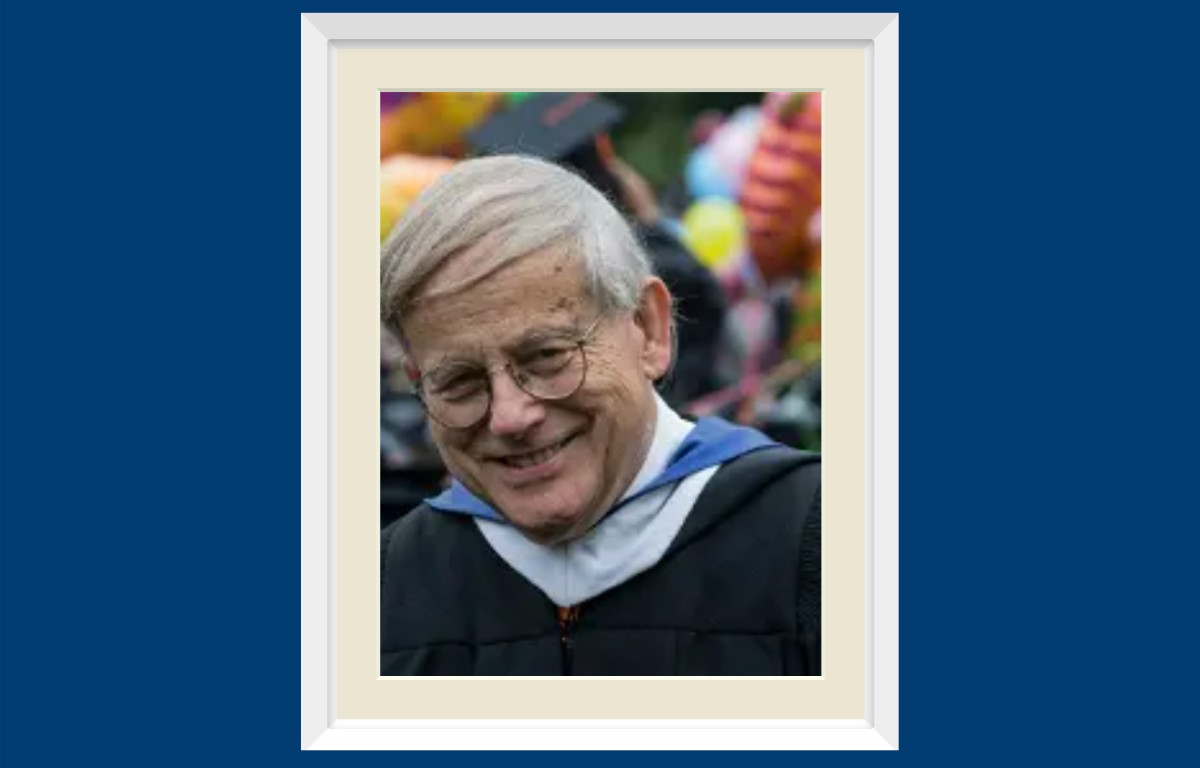

Alexander “Sandy” Gilliam, who served the University of Virginia in many capacities over 40 years — including advisor to four presidents — dies at 91

Alexander G. “Sandy” Gilliam Jr. had a long and storied career that took him halfway around the world working in counterintelligence, first in the U.S. Army, then in the Foreign Service, and finally in the State Department in such far flung places as Israel, Africa, and throughout the Middle East, studying cultures, politics, international protocol, and languages — including Arabic, which he always lamented was far too difficult to master.

But his strong ties to Virginia – especially the University of Virginia tucked into the small town of Charlottesville in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains – kept tugging at him until 1975, at the age of 41, he headed home.

As the story goes, however, Sandy was still reluctant to return to work at UVA, thinking that some might see him as trying “to recapture the lost days of youth” in what had been an all-male university. It wasn’t until he saw a woman student emerge from his old room on The Lawn that he was convinced that important changes were underway. He took the job as special assistant for then University President Frank L. Hereford Jr., the first of many positions he would hold over the next 40 years, including serving as special assistant to University Presidents Robert M. O’Neil, John T. Casteen III, and Teresa A. Sullivan.

Sandy died on June 8, at the age of 91, at home with his devoted wife Katherine Scott by his side in the house filled with memorabilia from a lifetime of collecting books and artwork that they shared for 50 years. In an interview in 2004, he said, “I think for Virginians a sense of place, at least for my generation, is important. I began to realize my roots were stronger than I thought they were.”

“Everyone who has known the University and its people during the last 50 years has in one way or another known them through Sandy,” said University President Emeritus Casteen. “Sandy has been the essential interpreter of the place and its people, but only rarely its chief defender, and then when he was willing to be right while all around him were wrong. More often, he let folly run its course while waiting patiently to pick up the pieces. In his view of the University’s past, space for improvement was always there. He backed the authentic reformers, the people with visions, the sometimes isolated loners who saw truth where it was.”

Sandy was born May 4, 1933, in Baltimore, MD, to Alexander George Gilliam Sr. and Laura Edmondston Venning, and grew up splitting his time between Maryland and Virginia, following his father’s medical career, but Virginia always called his name. In fact, the one constant was his grandmother’s house in Charlottesville, just four blocks from the University, where he spent many childhood summers. There was never any doubt that the young Sandy would attend college anywhere else. The first Gilliam, he liked to recall, enrolled at UVA in 1829. Sandy graduated in 1955 with a degree in history – and eventually became a member of Beta Theta Pi fraternity, The Raven Society, The IMP Society, and The Seven Society, groups he remained deeply engaged with throughout his lifetime.

History was the perfect major for Sandy – who honed his skills as raconteur extraordinaire – and who liked nothing better than to dig into the recesses of memories and to tell stories. Most in the University community knew Sandy as a walking history of the University and of Thomas Jefferson lore – and if ever there was a question that needed answering, the first call was to him for reference and confirmation. His answers always came with great attention to detail and extraordinary humor – and delivered in a deep Southern cadence that was unique to him, but reminiscent of Petersburg.

Petersburg was home to his maiden Aunt Anne who lived next door to Katherine Scott’s parents, and who for years plotted to bring Sandy and Katherine Scott together, even inviting Katherine Scott, while home visiting family, to travel with her to Lebanon to meet Sandy. She politely declined.

It was sometime later, after the wedding of a Gilliam cousin that both Katherine Scott and Sandy attended, that Aunt Anne and Sandy were invited to supper next door, when Katherine Scott discovered that Sandy liked music, including classical. Katherine Scott, herself a musician, was surprised to learn that a “young man” might love music as much as she did. After two years of courting, they married in 1972. Two years later, Alexander G. Gilliam III was born, followed three years later by John Bolling Gilliam.

Alex and John, raised in Charlottesville in an intensely academic environment, chose different paths. Alex graduated from the University’s School of Architecture, while John headed to West Point. But for Sandy and Katherine Scott, it was always about the importance of education, not necessarily the place – and what made their sons happy. Sandy spoke often of how proud he was of his sons’ choices and career paths – and of his deep love for his five grandchildren, all of whom brought him great joy during his last weeks.

At the University, Sandy immersed himself in mentoring students while juggling many titles: Special Advisor to presidents; Secretary to the Board of Visitors; Protocol Officer; and University Historian. He also served on endless committees — Finals Weekend, Reunions, Founder’s Day, and numerous Special Events committees. He was everywhere at once — a regular sight striding across University Grounds like he owned the place. It was his job as secretary to the board, however, where he focused his greatest energy for 18 years.

“In a room where deliberating members might want to think about their powers, which can be considerable when they are assembled in a proper session,” Casteen said, “Sandy taught the enabling disciplines of obligation and responsibility — the board characteristics that confer greatness on institutions and their governing boards. Gently and quietly, like Mr. Bice before him, Sandy enabled our boards by teaching them their limits and their responsibilities before their powers.”

When dignitaries came to visit the University – Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, Presidents George H. W. Bush and Ronald Reagan, Mikhail Gorbachev, a handful of Nobel Peace Laureates, including the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu to name a few – it was Sandy who worked behind the scenes helping to manage security and protocol issues, and to coordinate with international partners to assure that all visits went without a hitch.

But if you visited him in his Rotunda office – surrounded by dozens of framed photographs and memorabilia, each with its own story – there was usually someone seated across the desk being schooled by Sandy. He was exceedingly generous with his time to all members of the University community. He never seemed hurried but focused on the individual – from callow first-year students and long-time administrators to the most senior of alumni. He believed it important to merge student and faculty communities in public service endeavors as well as joyous camaraderie. And because of his own travel history, he encouraged studying abroad, including the UK Fellows that paired UVA students with British prep schools for a year of teaching.

He was a friend and colleague to generations of students, many of whom kept in contact with Sandy and Katherine Scott over the years, but more so during Sandy’s year-long illness when they came to entertain with stories of their undergraduate hijinks and those times he was called on to extricate them from a certain situation. These were the same students who he’d often brought home to Katherine Scott — with scant warning — for robust conversations and home-cooked meals that often ran six courses and late into the night. Numerous former students recall Sandy’s infamous tomato ice cream with a mixture of awe and disbelief.

A “foodie” long before the term became popular, Sandy did love to cook, creating traditional Southern meals using his mother’s hand-written recipes, as well as exotic, spicy dishes from the places he had lived abroad.

He knew all the best barbecue joints from Virginia to Texas, which he’d quickly rattle off if he found you might be traveling in the vicinity of any of his favorites. He was always ready to drop everything to take a novice connoisseur on a ride to Petersburg for an initiation at King’s “famous” barbecue hut. (No one had the heart to tell Sandy that after 80 years, King’s closed its doors last summer.)

When Sandy “officially” retired in 2009, he was praised for his “great competence, wisdom, and devotion,” but also for his building deep relationships across the University and the knowledge he shared so freely. Despite closing that 39-year chapter, he was easily convinced to stay on half-time as both the history and protocol officer.

In fact, it was a little more than a year ago, on a cold January evening when he was rushing to make a speech on University history to The Raven Society, that Sandy stumbled and took a bad fall on the brick walkway not far from his old office in the Rotunda. That fall triggered many problems and over the past year he struggled with his health. But he had been on a mission — even at 90 — to do one of the things he still loved most, and that was to serve the University.

At Sandy’s retirement, he received a prolonged standing ovation from members of the Board for his service. Asked to say something in response, Sandy — seldom at a loss for words — replied simply: “It’s been fun.”

Sandy is survived by — and will be greatly missed by — his wife Katherine Scott Gilliam; his son Alexander G. Gilliam III, and his wife Renee Schacht; his son U.S Army Col. John Bolling Gilliam and his wife Erin; his five grandchildren: John Gilliam, Virginia Gilliam, Jackson Gilliam, Quinlan Gilliam, and Alexander G. (Scout) Gilliam IV; his sister Laura Edmondston Gilliam; his sister- and brother-in-law, Mildred and Joseph Herget; and a huge following of friends who will be retelling Sandy stories for many, many years.

For more on services and to share your condolences, visit Hill and Wood Funeral Service.